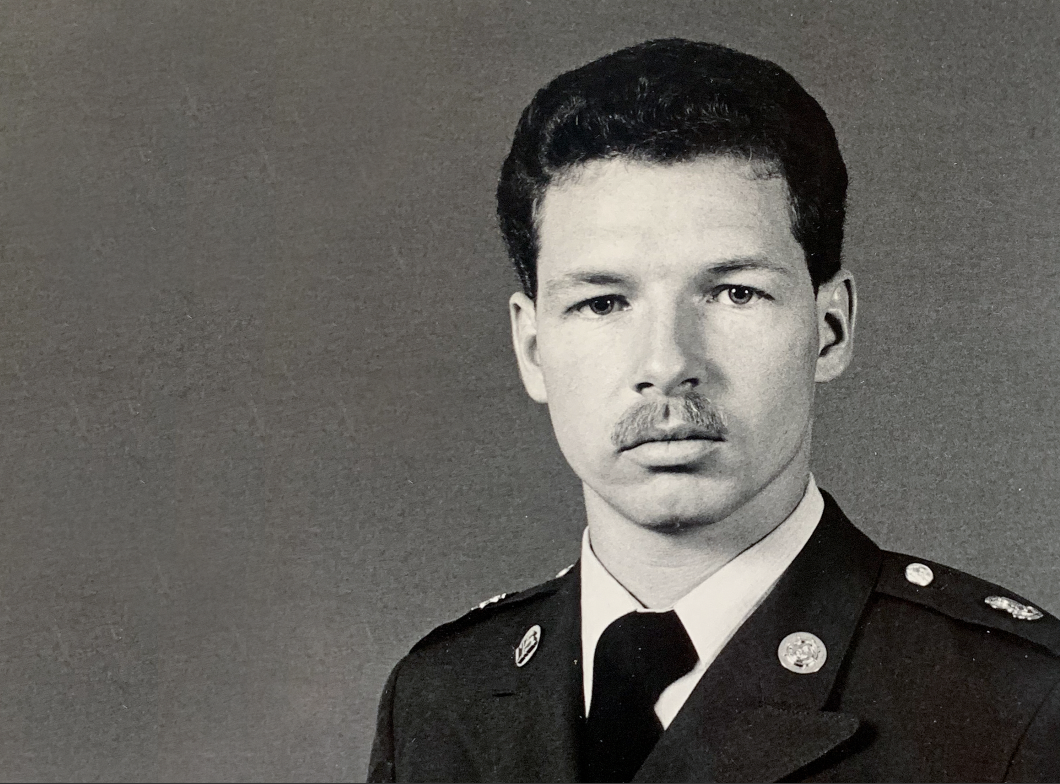

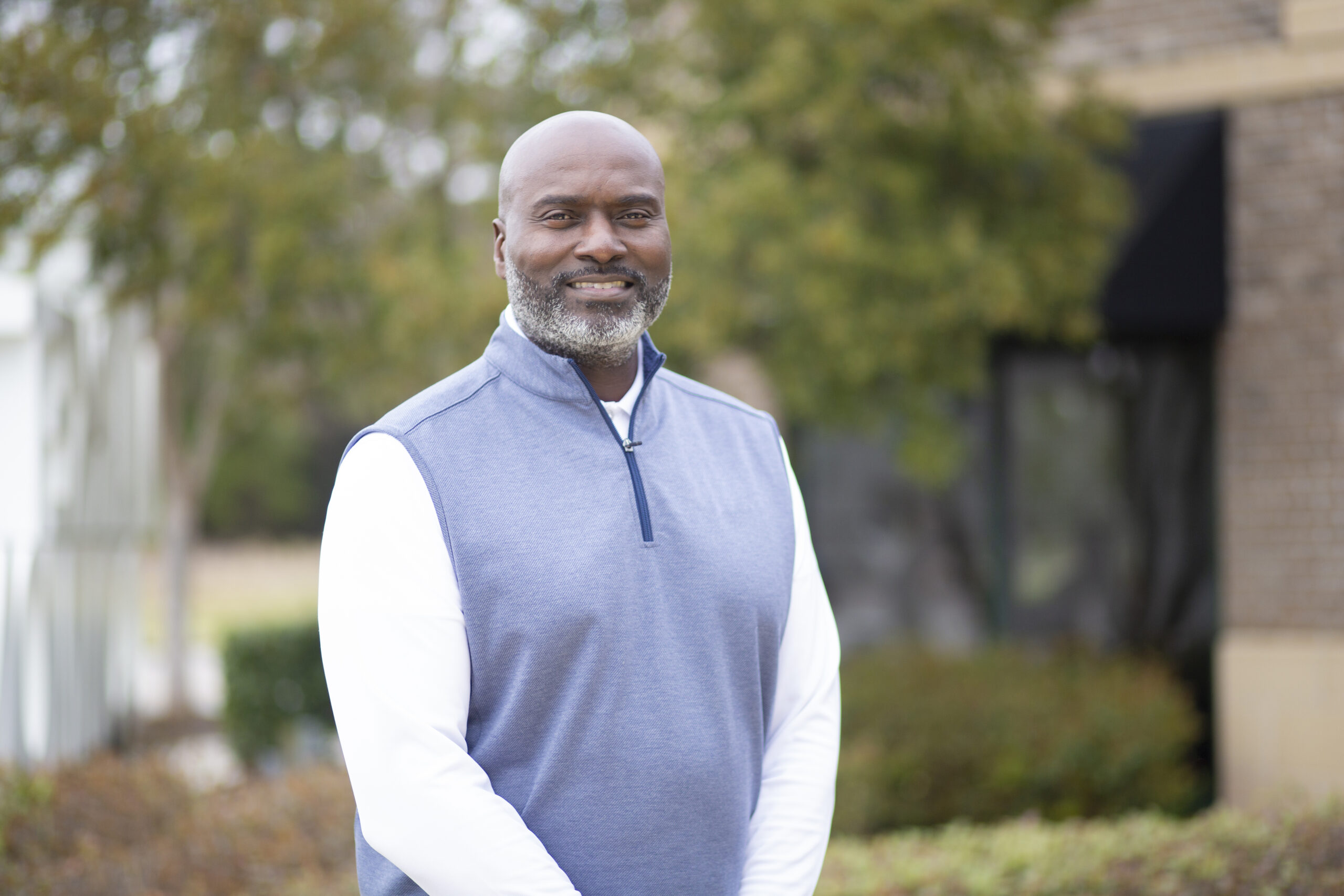

William Oscar Warren Jr., Part 2 of 2

Born in the Roaring ‘20s — U.S. Air Force Airman 1st Class, Farmer & Epic Traveler Celebrate Our Veteran gives voice to the stories of the U.S. military veterans living amongst us. The actions of these brave and dedicated people, who have served our country both in active military duty as well as administrative positions, have and continue to contribute to the protection and preservation of us and our country. We hope that this section of our paper is an opportunity for our community to hear and see veterans with new eyes, and for veterans to receive recognition and honor for their experiences and life journeys. This month’s Celebrate Our Veteran recounts the story of William Oscar Warren, Jr., known to his friends as WO, as told in his own words. This is part two of a two-part series, continued from last month. Click here to read Part 1. by Melissa LaScaleia Continued from last month…. “On Monday I went to the order room to check in, and the sergeant said to me, ‘What are you doing here?’ And I said, ‘I’m signing in.’ And he said, ‘I already signed you in. I knew you’d be here. Take your wife and go home and get settled and come back tomorrow morning.’ After graduation, I was going to be sent to North Africa for my duty assignment, but my wife was about 5 months pregnant, so they sent me to Donaldson Air Base in South Carolina instead. I found out that they had a detachment at Pope Air Force Base in North Carolina, 25 miles from my home. And I explained my personal situation to my sergeant and he agreed to send me there for my regular duty instead. I was able to live at home and drive into work every day. This was during the Cold War era, so we were always expecting to be attacked by somebody. I worked behind a big wall of plexiglass, and any information I had, I had to write backwards so the commanding officers in front of the glass could read it. It took some practice to get good at that, but it wasn’t as hard as I thought it would be. My days were a combination of studying radar, working behind the plexiglass writing, and working on what was called a height finder, to discover the whereabouts of enemy planes. One night about 2 am, I was on radar duty; my radar scope was covering 500 miles in all directions. I saw a blip come up on the edge of my scope. I immediately started to track it, but when the needle had rotated around one time, the dot was in the center. Then the next time, it was almost off the screen. It got my attention, so I called it in to my headquarters, Shaw Air Force Base. They had picked it up too, but also couldn’t identify it. I kept a log book of my recordings that I wrote out by hand, this was the era before computers, and I recorded it as an unidentified flying object. We never knew what it was, but it was moving fast. Everything went pretty smoothly during my time in the military. We went on what was called maneuvers in 1955, in Louisiana and Texas for three months. These were joint Army, Navy, and Air Force mock war training operations. We packed up all our equipment and loaded up a convoy that we took to Louisiana, doing what we did in North Carolina, scanning the skies. In the mock encounter, somehow a plane got through our system, and in the exercises we were all killed. Once in the service, I really enjoyed it, and was thinking about staying in. I made Airman 1st Class in twenty-two months. I had 26 months to make staff. But then I found out that as a radar operator, you can’t make staff your first enlistment. I was kind of disappointed. I decided to leave the military early because the government had too many enlisted men and they were letting 600,000 men out early if they wanted to go. My father wanted me to come back home, so he offered to build a service station with all expenses paid, for my brother and I to run. I decided to take the offer, and signed up with Philips Petroleum company in 1957 after I was discharged. Then I got into the oil business, running delivery for kerosene, gasoline, and fuel oil. We delivered anything from 5 to 150 gallons at a time to tanks in people’s yards or on their farms. We also built two more stations that we rented out, and sold Phillips 66 gasoline to other stations. We stayed in the business until 1996. Then we sold it, and my wife and I bought a van and started traveling. We covered all fifty states, all over Nova Scotia, and parts of Mexico and Canada. While we were traveling, we were still managing farmland from afar. I was on the board of the Erwin Voluntary Fire Department for over fifty years, as director. I did it as a civil servant, and they gave me a plaque to commemorate my service. I started playing golf when I was thirty years old, and played until I was ninety-three when a sciatic nerve in my right leg started to bother me; I never got over it and lost interest in the game. We were traveling until 2010, then we kind of slowed down. We’ve still done a bit of traveling since then. My wife wanted to spend more time in Myrtle Beach, SC, so we bought a park model camper at Myrtle Beach Travel Park. We spent part of our time in Myrtle Beach, and the other part of the time in Erwin. We were staying in our own home in Erwin until two months ago, when my wife broke her hip. She’s using a walker now, doing physical therapy, and my eldest daughter didn’t think … Read more