Major General Charles Baldwin, Chaplain of the MBAFB

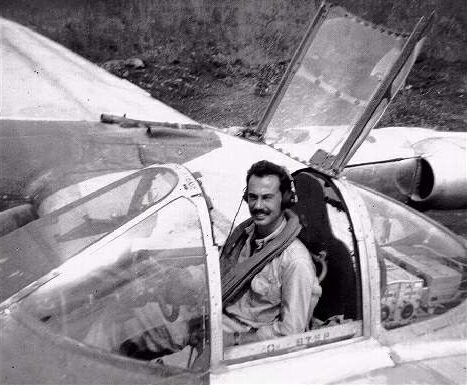

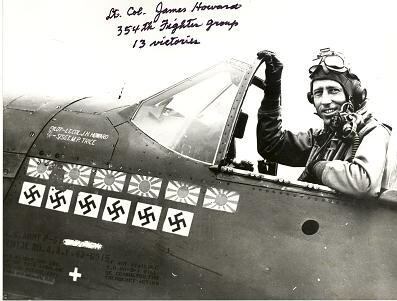

by Melissa LaScaleia Baldwin Lane is a short street in the Market Common that turns into Shine Avenue and runs parallel with Pampas Drive. It intersects with Mallard Lake Drive, the road that leads to the Barc Park South, dog park. Baldwin Lane is named after Major General Charles Baldwin, who was also a chaplain with the United States Air Force. Charles’ professional studies and career have taken him all over the world— to Saudi Arabia, Italy, Germany, Texas, California, Thailand, and Washington, D.C., just to name a few. Charles Cread Baldwin was born on April 7, 1947, and grew up in New Haven, Connecticut. He graduated with a B.S. from the U.S. Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colorado, in 1969. He was assigned as an EC-121 pilot, then sent to helicopter pilot training in Fort Rucker, Alabama. He served in the Vietnam War, where he was an HH-53 rescue helicopter pilot in South Vietnam. In the mid ’70s, he returned to the United States and life as a civilian for a short time. He attended the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, where he received his master’s degree in divinity, and became a minister. When he returned to the military in 1979, it was as a Protestant chaplain. He also completed Air Command and Staff College, as well as Air War College. Some of his assignments as chaplain included posts in Decimomannu Air Base, Italy; senior Protestant chaplain for the U.S. Air Force Academy, in Colorado Springs, Colorado; and Office of the Command Chaplain for the U.S. Air Force European Headquarters in Ramstein, Germany. Baldwin also served as the senior chaplain for the Myrtle Beach Air Force Base from June 1989 – June 1992. During his tenure in Myrtle Beach, he accompanied the soldiers of the 354th Tactical Fighter Wing to Saudi Arabia, on their Desert Storm deployment. Baldwin became Deputy Chief of the Air Force Chaplain Service in 2001, and was stationed in Washington, D.C. In 2004, he became the Air Force Chief of Chaplains, also in Washington, and earned the rank of Major General. As the Chief of Chaplains, he offered advice about moral, ethical, and religious issues that pertained to all members of the Air Force. He was the senior pastor for over 700,000 servicemen and women in the United States and abroad, and led chaplain services for the Air Force’s 2,200 chaplains. He also acted as one of the advisors on religious, ethical and moral issues for the Secretary of Defense and Joint Chiefs of Staff. Baldwin has received numerous medals and awards to commemorate his service and achievements including: the Distinguished Service Medal with oak leaf cluster; the Legion of Merit with oak leaf cluster; Distinguished Flying Cross with oak leaf cluster; Bronze Star Medal; Meritorious Service Medal with silver oak leaf cluster; Air Medal with three oak leaf clusters; Air Force Commendation Medal; Air Force Outstanding Unit Award with “V” device and oak leaf cluster; Vietnam Service Medal with three bronze stars; Southwest Asia Service Medal with two bronze stars; Global War on Terrorism Service Medal; Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross with Palm; Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal; Kuwait Liberation Medal; and the Kuwait Liberation Medal. Charles Baldwin retired from the military in 2008. To read more of our history features click here.